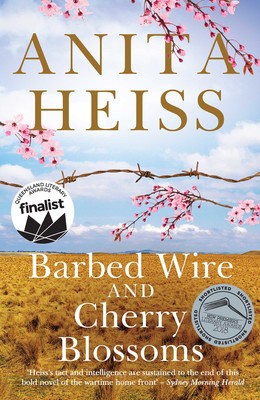

‘Barbed Wire and Cherry Blossoms’ is an historical fiction novel set in Australia in the last years of WW2. On the night of 3 August 1944, over 1,000 Japanese broke out of the Prisoner of War camp in Cowra, New South Wales. The story unfolds over the next year and ends at the conclusion of WW2.

The time and location for this novel is all important here. Underlying the story are cultural norms operating at that time. These include the Australian government’s treatment of Aboriginal people and the Japanese government’s and a Japanese family’s expectations of human behaviour. These weave throughout the novel, informing and prodding readers to consider the ‘right and wrong’ of these cultural norms.

Close to the Japanese prisoners’ camp in Cowra is Erambie, an Aboriginal people’s community. The community is close-knit and lives under the Australian Government’s ‘Aborigines Protection Act’, which operated at that time. This Act imposed many restrictions on the Aboriginal people at Erambie and descriptions of these run through the novel. Parallels are drawn between these and Hiroshi’s social restrictions dictated by his government and his family.

As the story opens, Banjo Williams discovers the escaped prisoner, Hiroshi, hiding beneath his Erambie veranda. What to do? Banjo’s Aboriginal family and community Elders decide to hide the escaped Hiroshi. The often-lengthy reasons behind this and other decisions and actions tend to weigh the story down at times despite their admirable purpose to inform and educate readers unfamiliar with the social realities of these times.

Nightly, Banjo’s daughter, Mary, takes food to Hiroshi. Slowly the two come to understand a little of each other’s culture. Gradually over a year, Hiroshi and Mary reveal the restrictions imposed by their respective countries’ governments and families. Mary and Hiroshi are attracted to each other but recognise the unlikelihood of a future together.

An Epilogue, dated 13 November 1964, features the inauguration ceremony for a new Japanese war cemetery on the site of the old Cowra prisoner of war camp. This ceremony provides closure to the relationship established in 1944 between a young Aboriginal girl, Mary Williams, aged 17 years of age, and Hiroshi, an escaped Cowra prisoner, aged 25 years.

In the book’s Acknowledgments, the author describes her research undertaken for this novel including that her mother, Elsie, shared her own stories of growing up at Erambie. Heiss states, ‘Wherever I am in Australia or overseas I am always Wiradjuri. My connection is to my country, my people, the land my mob has always come from.’ (from Anita Heiss’ memoir, ‘Am I Black Enough for You?’)