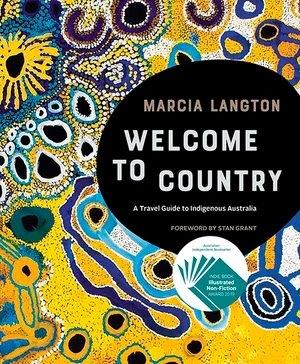

Right from the lush, tactile cover, with its powerful names - Marcia Langton, Foreword by Stan Grant - and its high end production values, ‘Welcome to Country’ invites readers inside. But then the questions begin. If the book is by Marcia Langton, then why is two-thirds of it written by two Aboriginal students, barely acknowledged in the end matter as Nina Fitzgerald and Amba-Rose Atkinson? And what is a distinguished anthropologist and prominent activist doing writing a travel book anyway?

‘Welcome to Country’ feels like two books in one. First, a series of essays under the heading ‘Introducing Indigenous Cultures’. They range from brief general pieces on Art, Performance and Music, for example, to the more challenging essay on Kinship, illustrated with diagrams that perversely make a challenging subject even harder. (Trying to achieve clarity in just four pages was optimistic at best.)

These essays are of course authoritative, and along with the expected strong statements about Land Rights and the Stolen Generations, also tackle questions that are not raised in other books: ‘What if your Guide is Not Indigenous?’ for example. Their academic basis is made more accessible by Langton’s frequent inclusion of her personal preferences in Aboriginal culture. The essay ‘Storytelling’ is a list of her favourite authors: Kim Scott, Alexis Wright, Bruce Pascoe, Leah Purcell. But inevitably these raise more questions than they answer. With space to mention only a few, the list of authors will have experienced readers wondering why it doesn’t include younger, edgier artists. What about storytelling through hip hop? Animation? The questions continue. And that’s not necessarily bad.

The concept of the book itself, however, is a tough call, and occasional slips suggest that the author could have been better served by her editors. When she abbreviates Sir Ronald Wilson as ‘Sir Wilson’, appears to fuse Whitlam government policy initiatives with the new Liberal National government elected in 1975, and denounces a misreading of one rock painting image as attributing ‘sexual deviation’, the vast scope of the brief here seems to be slipping from her editors’ hands, if not her own.

The question of why this eminent anthropologist agreed to write a travel book is more interesting. The pause on international travel created by the COVID-19 pandemic brought into sharper focus increasing challenges to the enterprise of mass tourism generally. Great monuments to material culture from the Taj Mahal to the Sistine Chapel are being loved to death. How much more vulnerable, then, is the natural environment at the heart of Australian tourism? Langton’s response is bold, but risky. Managing tourism properly might be an opportunity to educate non-Indigenous people, to monitor protocols and to ensure funding for the maintenance of sites that are both accessible and forbidden to the general public.

The travel book section of ‘Welcome to Country’ is written in a completely different tone. It gives detailed guidance to those interested in the proposition that tourism might preserve Indigenous culture. Each state is given a chapter. Perhaps predictably, the most extensive coverage is devoted to the Northern Territory. Seasonal advice is provided, comments on physical accessibility, along with opening hours, admission prices, even phone numbers, and special points of interest that tourists are advised not to miss.

All this is painstakingly researched, but two questions: is a beautifully designed hardback book the right platform for conveying travel information that is already out of date and could be better edited and consulted online? And, second, for the purposes of this database, how is such a book to be best used in schools? Answering the first question is easy. There are good reasons that most travel guides are produced less lavishly: to be really useful they need to be thumbed all day every day on the road, and at the end of a trip they will be discarded, because they take up unwanted space in a traveller’s luggage, and because next time they might be needed, the information will be out of date.

What role might ‘Welcome to Country’ have in schools? Marcia Langton’s section will inspire further research on particular topics, though the endnotes are not as helpful as the curated list of references in ‘The Little Red Yellow Black Book’, for example. Its design, while attractive, is not aimed at young readers - but then, neither is most of the content. And the travel section? There are definitely ideas for inexpensive independent backpacking here, but again the assumption in most of the entries is that readers will be adults with the budget to pursue their cultural interests. ‘Welcome to Country’ treats all aspects of its brief with respect. That alone is worthy of praise, if no longer unusual. From time to time it does lift its appeal above the level of browsing with genuinely helpful insights - Langton’s information about the process of welcoming visitors to country, for example. But reservations about its content and its usefulness start at the conceptual level. Langton herself is not wholly responsible for that, but sadly the book as a whole doesn’t finally overcome them.

In 2019, an adaptation was published: ‘Welcome to Country: An introduction to our First peoples for young Australians’ (ISBN 9781741176667). Although still under the imprint Hardie Grant Travel, it excludes the travel guide, which occupies two-thirds of the original. Langton’s text has been simplified and in some chapters extended. The chapter on Indigenous Knowledge is a welcome addition, with its account of traditional healing, fire management and cosmology. In place of the previous sideswipe at ‘sexual deviation’, an extended breakout on sexual diversity has been added. And there is a fascinating graphic on the language of mental health. Minor updates have been made in notes on the arts, but given the significance of children’s literature in the syllabus, it is bizarrely given just a short paragraph of 100 words under the heading ‘Children’s Literature’.

So in some chapters, concessions to a very different audience have been made in repackaging ‘Welcome to Country’ for young people; in other chapters, not so much. The most disappointing aspect is that the original book’s production values have been abandoned. The integrated, now black and white, photographs are grainy and in some instances barely readable, and the only colour is a bind-in of eight colour plates right at the end of the book’s 220 pages. This reflects poorly on the publisher’s attitude to the project. Advice to educators? Include both the original and the adaptation for younger readers in your collection. And urge Langton’s publishers to honour her subject matter and her readers with a better job next time.