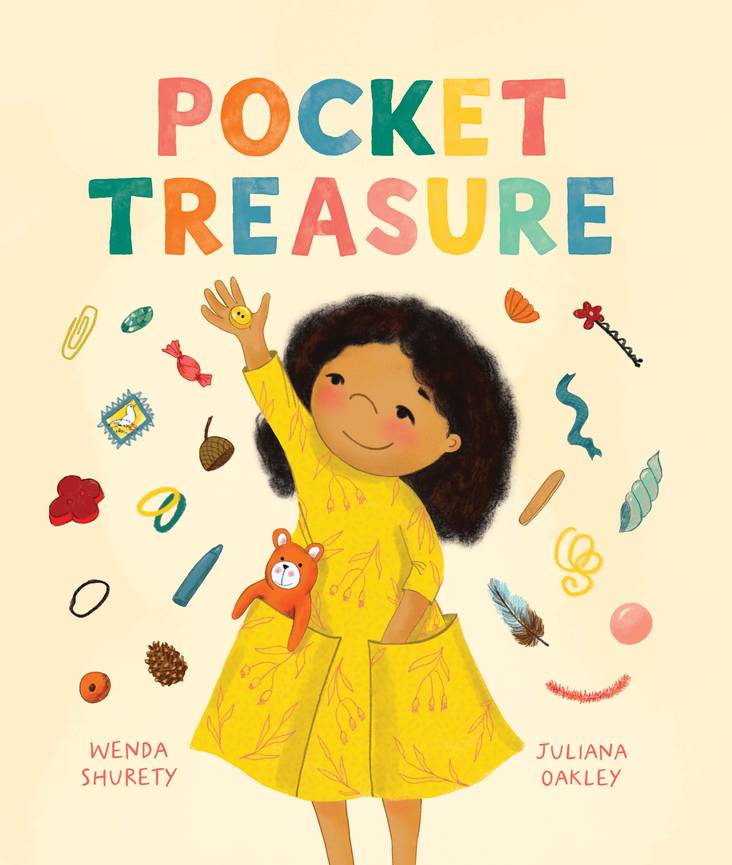

Although the text of ‘Pocket Treasure’ specifies a pre-school setting, and the front cover illustration seems to confirm that with a teddy bear smiling out from a young girl's pocket, the subjects of inclusion, mutual generosity and community will be appreciated by early childhood readers generally. Allira's favourite dress might not be fashion-forward, but she loves its two huge pockets because they hold all the treasures she collects during the day.

As the front cover indicates, what is in Allira's pockets might not be called 'treasure' by anyone else: a feather, a crayon, a button, some pipe cleaner, and so on. But as every parent or teacher of a preschooler knows, these are the construction materials of unique artworks. The children and their teacher Miss Garrett discover they need some item to complete their creations, and Allira digs into her pockets and finds just the thing. Allira is so generous with her treasure, however, that when she needs the perfect decoration to top off a mudpie for Miss Garrett's birthday, her pockets are empty. Each of the friends she has helped contributes some treasure of their own, and their communal action saves the day.

Young readers might like to discuss the old saying, 'What goes around comes around’. Allira is generous with her belongings and her empathy, and her friends are generous in return. So ‘Pocket Treasure’ is about community, the social contract - and the illustrations convey the multi-cultural diversity of this class. Pockets are private spaces, like cubby houses, bedrooms, garden sheds, lockers, diaries, backpacks. They are places to store things and ideas that perhaps no one except the owner will understand.

Young readers might look at picture books about sharing and community by Indigenous authors such as Aunty Joy Murphy, or Aunty Fay Muir, and by non-Indigenous authors such as Jeannie Baker, and use them to help young readers explore a reading of Allira's story as the story of Aboriginal generosity.

Because many of the children's activities in ‘Pocket Treasure’ centre on art or craft, Allira's pocket is furthermore an image of the imagination. Like the artist, who takes scraps of ideas from the private storehouse of their mind, and shares them with others who will help to make from them a unique new work. The artist and her community collaborate to create meaning. But the coda provided by the closing endpapers adds one more layer to this story. The names of the main characters are glossed with the meanings in their original languages, Celtic, Arabic, Mandarin, Swahili, Persian. They are all names for precious jewels. And the caption under Allira's portrait tells us her name 'is the word for ‘quartz crystal’ in some Indigenous Australian languages. This sends us back to reconsider Allira's appearance and actions. Although the text does not specify that she is Aboriginal, her hair, her complexion, and now her generosity, creativity and community mindedness invite a new reading of this heartfelt and charming story.