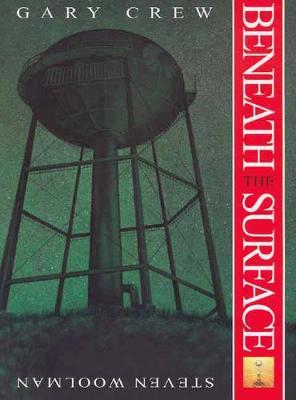

‘Beneath the Surface’ (2004) by Gary Crew and Steven Woolman is the sequel to ‘The Watertower’ (1994), which, although an award-winner, doesn't even come close to the mastery of illustration Steven Woolman achieved in the years between the two publications and before his untimely tragic death in 2004. Although it doesn't quite stand alone, ‘Beneath the Surface’ is a strong example of the mystery and resistance to narrative closure that Gary Crew made his own across several genres in the 1990s and into the 2000s.

For readers who have not been able to get hold of ‘The Watertower’, one former student has posted an outstanding detailed reading on YouTube under the name KellyVision, amply demonstrating why this book will not leave him alone, even though he first read it at school years ago. The plot focuses on Bubba and Spike, two boys in an Australian outback country town called Preston, who try to escape the heat by climbing up to the top of the watertower and swimming in its strange green water. When Bubba loses his clothes, Spike runs back home to collect some to replace them, but when he returns Bubba has changed and now has the terrifying stare of an alien in a science fiction horror movie that the townspeople have too. Clearly there is something sinister in the water that has affected all of them and the corporate image of an eye on the side of the water tower recurs with unsettling frequency throughout the narrative. Who or what is behind these changes?

Twenty years later, Spike returns to Preston unrecognised. He is now Doctor Trotter and is told that there is no need for a doctor because no one in this town ever gets sick. But he is not that kind of doctor: he is a hydrologist and is on a mission to analyse the water in the tower and understand why it has exerted such power over the people. At first, he cannot find the watertower, because everything is wreathed in fog - a phenomenon strange enough in such a hot dry location. When he eventually gropes his way through it, he realises that the tower is not as he knew it in childhood. It is still stands astride Shooter's Hill like some alien spaceship come briefly to rest, however it is no longer rusty red but has a freshly polished gleam. Who would have cleaned it up and why? The water inside is colder, darker than Spike remembers and there is now no trace of algae. When he tests the water, there is not even a microbe. It is utterly clear and sterile. When he takes a single sip, the narrative closes with the words that this is 'his end, and his beginning', but if that is not sinister enough, one brief sentence sends us back to examine the other characters more closely: 'One sip, they allowed him.' Who are 'they'? Perhaps the strange looking board members who stare out at the reader from the second last spread. Or perhaps all the characters in the book with that unsettling glint of light at the centre of the eye where a black pupil should be.

A startling feature of the design in ‘The Watertower’ is the changing orientation of the layout. Readers must turn the book clockwise to read the horizontal axis vertically. ‘Beneath the Surface’ repeats this design trick, which deftly dramatises the need for a change in perspective if readers are to understand what is going on. But after Spike's nightmare, the orientation changes again, as what was unfamiliar becomes normalised although the design again uses tiles from the eye-shaped corporate icon as vignettes edging around its almost complete circle to contrast constantly shifting parallel locations.

Whereas ‘The Watertower’ interrogates changes in Preston itself, however, in ‘Beneath the Surface’ as the word text stays with Spike's investigations in Preston, Woolman's illustrations go much further afield: to a space observatory, some beach with a sign advising that the water is polluted, a swimming hole on Aboriginal land, a vast field of what may be canola being harvested, a Buddhist temple in southeast Asia, an underground mining operation, a private school for gifted children, a south Asian village where water is being decanted, a wet dark hangout for skaters in what may be the United States (from the fire hydrant almost out of frame), and a corporate boardroom that looks more like an alien council or satanic cult with Dr Spike now as a horned devil. In all these locations, the disturbing eye-shaped icon is embedded endlessly in the environment and the eyes of the people look out at the reader with a steady gaze that appears alternately vacant and malevolent. Young readers familiar with the character Chucky from the ‘Child's Play’ horror movie franchise will recognise the look.

Are we reading too much into this imagery? Are we 'overthinking' it, to use a contemporary expression? A tempting hypothesis is that for Gary Crew overthinking does not exist. Adult readers will recall Joseph Heller's mid-20th century political conundrum: 'Just because you're paranoid doesn't mean they aren't after you.' Or is there really some corporate - or even alien - conspiracy that has taken control of water resources and consequently every aspect of human life, with the purity of the water the perfect means for denying malevolence? This brilliant picture book - unexpectedly ahead of its time and tuned perfectly to today's viral mis- and dis-information on social networks - is about the way the mind deals with mystery and attempts to construct meaning from it. There are no answers in ‘Beneath the Surface’, but as the poet e e cummings says in a very different context, 'always to the beautiful answer the more beautiful question'. The power of the visual narrative here surpasses even Crew's seductive word text and would make an interesting comparison with a picture book such as Chris Van Allsburg's ‘The Mysteries of Harris Burdick’ (1984).