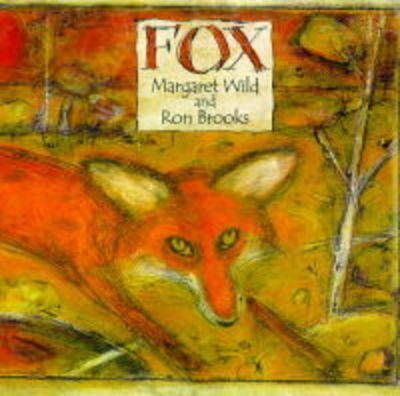

Perhaps it is due to an apocalyptic sense of foreboding around the end of the millennium, but ‘Fox’ by Margaret Wild and Ron Brooks is one of an increasing number of Australian picture books that feature catastrophic bushfire as a major plot point. Here the fiery orange of the cover, endpapers and half-title page gives way to the burnt-out detritus of the first few spreads, which are the colour of dust or sand, almost monochromatic and bleeding into the coat of the protagonist, Dog, as he tears across the page with what appears to be a dead bird in his mouth.

But the bird is not dead. Magpie's wing has been burnt in the fire, and Dog is taking her to the safety of his cave, where he can help her to heal. Magpie has only one good wing, and Dog has only one eye, so perhaps they can help one another to survive. The narrative begins to explore friendship as a form of symbiosis, inscribed in mythological hybridization. With Magpie perched on his back, Dog sees reflected in the river a strange new creature, half bird, and half dog: Magpie can be Dog's eyes and Dog can be Magpie's wings.

When the rains come and the bush begins to recover, a third character, Fox, enters and disturbs the harmony that has developed between them. He tries to separate the friends by persuading Magpie that he can run faster than Dog and truly make her fly as she desires, and eventually he succeeds. He convinces Magpie that what she has been doing up till now is a poor imitation of flying and he takes her on an exhilarating ride through the forests, plains and saltpans, out into the fiery desert - where she is surrounded by the intense orange glow that the desert shares with Fox's coat. But then he dumps her. He tells her that now both she and Dog can have a taste of the loneliness he has experienced, and he abandons her. Magpie hears a distant cry 'of triumph or despair' and despite the easy option of staying in the desert and disappearing altogether, she realises where true friendship lies, after all, and starts her long journey to find Dog - back home.

With a word text that is both pared back and highly poetic, ‘Fox’ is reminiscent of mythopoeic storytelling. Like ‘Aesop's Fables’ or the ‘Panchatantra’, it seems to invite anthropomorphic readings of its animal protagonists, but its complex layering resists allegory. Clearly, the story is about friendship and jealousy, but whereas other narratives for young readers resolve a threatened pairing of two characters by the ultimate inclusion of an Othered third character, here the exclusion of Fox is permanent and self-imposed, so there is no comforting resolution. Two indeed proves to be company, and of the pairings explored in the narrative, the only enduring one is the original friendship between Dog and Magpie.

The layering of both illustration and design, and the constantly shifting orientation of the word text - particularly in the first three spreads - invite us to focus on the layered meaning of the words and to keep responding to the changing perspective. Having only one good eye, or not being able to fly are straightforward enough, but what are we to make of Magpie's feeling that she is 'melting into blackness', or Fox's rich red coat that 'flickers through the trees like a tongue of fire' or Fox's 'smell of rage and envy and loneliness'? Wild's choice of animal species for her characters - one native, one ancient enough to be assumed native, and one notoriously introduced - suggests a cross-cultural reading about belonging.

But once again meaning is contingent. If this is partly a fable about the sly destructiveness of invasion, with Fox as the European intruder, how do we read the mirroring of Fox and Dog? Brooks gives Dog a bushy fox-like tail, and on pages 8-9, where Dog looks at the reflection of this strange new hybrid dog-bird creature in the river, Dog's head is given the sharply triangular large-eared proportions that lingers from the mesmerising image of Fox on the book's cover. So Fox becomes a kind of projection of fear lying deep inside Dog. Brooks did the lettering for the word text using his left hand, not the hand he writes with, to access the unconscious, with the result that the words appear to have been scratched with some ancient instrument, or with the claw of an animal, or by a child who is still developing fine motor skills. And the design which assembles and rearranges grabs from the word text scratched onto scraps of paper again dramatises the search for meaning. The integration of Dog and Magpie then appears to be in contest with the isolating force of the conscious, represented by Fox.

The continuing allure of this picture book is its potential to be read in so many ways, and at different levels of reading confidence. Most of the reviews centre on the theme of friendship disrupted by jealousy, which is available to readers of lower primary school age, but for older readers and adults it quickly becomes an interrogation of the idea that hurt people hurt people, and with higher level thinking a quest for personal and cross-cultural integration - the meaning just slipping from the reader's hands as the three protagonists tear across its pages and across the vast Australian spaces.