‘Never Lose Hope’ is inspired by the true story of John Hudson, an orphaned boy of nine years, convicted of stealing a shirt and a few other items. He was the first child convicted at the Old Bailey in London and then sentenced to seven years and transportation. He arrived at Port Jackson in 1788, the youngest convict transported in the First Fleet. Two years into the colony’s existence, food in the new colony is running out and young John steals two apples. Now John is on his own, hiding in the bush at night and scavenging for food by day.

His life connects with that of Isabella Rosson, also a convict. Being able to read and write, she is more fortunate and becomes the teacher in Australia’s first school in the colony. The story premise is that Isabella taught John, an eager learner, to read and write over two years. Unfortunately, he is then caught and transported to Norfolk Island n 1790. Records show that John returned five years later to Port Jackson., but nothing more is known about this young man.

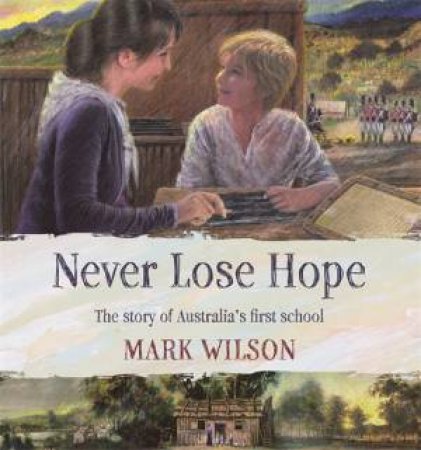

Mark Wilson’s artwork specialises in photo-realism. His use of acrylic paints on canvas and highly textured artwork brings people alive, captures the Australian landscape and details the colony’s hard life. Wilson’s double pages are filled with fascinating details of these times, here concentrating on two convicts, the teacher and a young boy. One is more fortunate. Illustrations of Australia’s first school in the colony give a brief glimpse into a classroom. Young pupils learn to write using a rectangle of wet sand on the floor and a stick to make their letters. The story centres on young John, a runaway convicted convict and Isabella Rosson, who inspires the young boy to learn to read and write and especially to be positive through her inspiring words, ‘Never Lost Hope’. Mark Wilson adds journal entries written by Isabella to provide an extra layer of historical detail about the treatment of convicts and the efforts of people such as Reverend Johnson and his wife Mary to try and help the convicts.

Mark Wilson comments on his art that he creates ‘line drawings sketched in as much detail as I can manage. I then use permanent markers, ink, pastel, watercolour and acrylic paint – and just about anything else lying around; each picture dictates the technique. I use a lot of photos, but for reference as opposed to directly, so although some paintings look like photos, they are not. (They are ‘super realism’, used to emphasise important moments in the story.’ (Robyn Sheahan-Bright Teachers’ Notes)

‘Beth: The Story of a Child Convict’ (Hachette, 2016) is a companion to this book. Mark Wilson has created a series called ‘The Convict Children.’