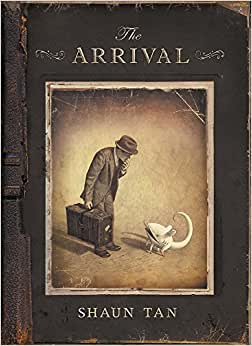

In 'Arrivals and Departures', his keynote address at the 33rd IBBY Congress in 2012, Shaun Tan says that for years he had been reading narratives of migration ranging across many places and times and wanted to somehow distil them into a single story, until he realised that although they had elements in common, such a reductive project would invalidate the unique personal experiences of each individual migrant. Rather than a standard picture book, ‘The Arrival’ (2006) eventually became a 128-page graphic novel, exploring the outer and inner lives of its characters, observing individuals and objects both in and out of context, in hundreds of images constantly shifting in format and complexity - all unaccompanied by words.

To call the narrative 'wordless', however, is not strictly accurate. Like Jeannie Baker's ‘Window’ and ‘Belonging’, ‘The Arrival’ has words embedded in the pictures - in some scenes there are letters, cards, passports, posters, maps and other documents, and the surfaces of the imagined city are literally covered with symbols and words - but they are in languages that none of us can read, thereby dramatising a common experience of migration. By resisting a word text, Tan makes the narrative unusually inclusive. Readers can access the images regardless of their language, age, ability or reading confidence. Tan says in 'Arrivals and Departures' that he always likes to leave his stories unfinished, because he regards his readers as collaborators in the creation of meaning.

Again, like the concept of wordlessness, however, the total accessibility of visual literacy is an illusion. Although the image on page 23 can be read simply as a crowded ship of migrants huddled against the cold, it is a direct reference to the iconic Australian 1886 painting 'Going South' by Tom Roberts, as acknowledged in the final ‘Artist's Note’, and there are references elsewhere in ‘The Arrival’ to well-known images of immigrants passing through Ellis Island in New York. Recognising those references is not essential, but it adds layers of meaning to Tan's story of migration by generalising time and place. And although readers have greater freedom to interpret, for example, the fantasy aspect of the city in chapter I, these images still call on the range of visual experiences we bring to them. Are they tentacles of some vast octopus curling around the terrace houses and casting shadows on the walls? Maybe - but the 'teeth' or spikes along the tentacles evoke past images of dragons, and when Tan himself refers to them as 'black serpents' in one interview, does he mean snakes as we know them, or is he thinking of medieval dragons, which were referred to as worms and serpents? In any case, our reading of both 'serpents' and blackness is culture-specific. As in other books by this author, any momentarily firm purchase on meaning seems to slip away from us and leave us groping for the next foothold.

I

Although ‘The Arrival’ is not autobiographical, Tan personalises the immigrant experience by using himself as a model for the main protagonist and by drawing on other members of what he calls affectionately his multi-species family, particularly his Finnish-born wife. Even the origami bird is an oblique reference to feathered family members, as well as a literary nod to Eleanor Coerr's book, ‘Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes’ (1987), symbolic of peace. In the first chapter, a family of three heads for a train, apparently intending to leave behind a troubled city, but only one of them boards it: the man. The woman and the girl return home, the only humans evident in an otherwise deserted street. Images of decay inside their house and in the streets outside provide symbolic motives for the departure. The splitting of a family, with one parent going on ahead to find work and accommodation, is a common feature of migration.

II

The fantasy thread in the opening chapter really takes off here, as the man undertakes a long journey by ship to the land of hoped-for opportunity. Three spreads depicting the clouds above the ship convey his shifting inner life: sometimes there appear to be objects imagined in the clouds; at other times there are just changing patterns. The origami bird morphs into a flock of flying fish, and when the travellers reach their destination, it is a city reminiscent of New York, but watched over by two colossus figures that reimagine the wonders of the ancient European world with physical features of the man and his wife from chapter I. After endless queues and a long repetitive sequence of health checks, interrogations and official stampings, the man is released across this bizarre city in a kind of capsule or pod, suspended from a huge hot air balloon.

Tan says in several interviews that being able to draw spaceships and monsters was a key to some degree of inclusion and even popularity in his own quite lonely and alienated childhood, and the dream cityscape in chapter II, that is part art installation, part fun park and part vision of the future suggests how desperately the protagonist in The Arrival is searching for a place that can become familiar enough to be called home.

III

Just as the platypus in Australia appeared to European immigrants to have been assembled from the remnants of other animals, a strange white creature from chapter II becomes the protagonist's companion. A mouse, a tadpole, a sperm, an axolotl? It mirrors the construction of the immigrant as unique alien, and the desire to leave uniqueness behind and blend into the new environment. This four-legged companion offers the kind of unconditional friendship that is rare in encounters with the two-legged species.

Chapters III and IV are more challenging than the opening chapters because they are longer, they feature more characters, and interpreting the action depends increasingly on reading metaphorically rather than literally.

The profusion of frames with sometimes minimal differences slows the action down. Visual and performance adaptations of ‘The Arrival’ that try to simplify the narrative by focusing on an individual frame rather than a sequence of frames completely miss the point of the graphic novel format here. First, the profusion of views conveys the complexity of perspective on the immigrant experience. To the newcomer, the strange community he arrives in is Other; but to that community he is Other. The process of alienation is mutual. And there are many additional points of view in time and space to be considered. Second, the phenomenon of new experiences racing past in a dizzying blur is common to migration, so Tan slows the narrative down in what are often freeze-frame sequences. Maybe if we take the time to observe and respond to individual moments, we will better understand the experience of Otherness overall.

There are three main sequences here. First, in taking a surreal and exhilarating excursion on a fantastic airship, the protagonist meets a young woman who has been cruelly exploited in one of the 'dark satanic mills' left over from the industrial revolution. Second, in his search for food, he meets a family who have escaped from some towering and horrific totalitarian regime to build a life of domestic security and creativity in a different location. Both sequences are punctuated by alluring and creative, light-filled images of the new land that is their quest.

IV

The third major sequence opens with the protagonist encountering a range of individual options as he looks for work, and finally the possibility of succumbing to the dehumanising work on factory assembly lines, which culminates in guild or class action of a military kind. It ends in war and devastation, but draws him on with light-filled utopian scenes, dominated by images of a diverse population at play. Although the tone of The Arrival is serious and often grim, the graphic novel form is often associated with a breathless pace, and with comedy, so the playfulness of many of the fantasy images, and the frequent use of paper construction and references to the visual arts in the narrative are metalinguistic reminders by the artist - almost notes-to-self - that with only an artist's tools he can actually help alleviate the experience of alienation.

V

The sending of a paper bird of peace, the passing of seasons and images of baby birds being fed in the nest bring the protagonist's wife and child to the new land, where they arrive and are reunited as a family in a domestic environment that replaces the bleak wintry greys with warmer nostalgia sepia tones, and the four-legged companion, no longer strange, becomes the child's constant playmate. Then the narrative comes full circle but advances by one generation as a new 'Arrival' asks the child for help with an inscrutable map and is given directions by a recent newcomer who is now at home.

This reading is of course just one possible journey through Tan's masterpiece, and although there is a logic to each of the sequences and the narrative as a whole, the withholding of an accompanying word text creates both the silence which is both imposed on the arrival by the alien community, and the silence that is self-imposed as a response. It also empowers the newcomer with a greater opportunity to overcome the mutual Othering of this experience and create meaning through a different kind of literacy.