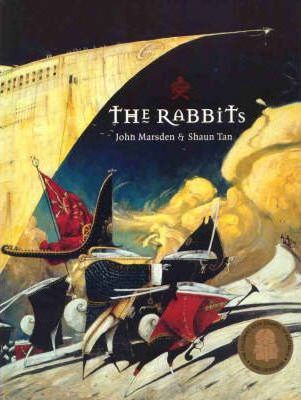

Although neither the author nor the illustrator of ‘The Rabbits’ has First Nations cultural heritage, they bring to this fable about colonisation their extensive experience as authors for young people, in particular the investigation of the dispossessed in their respective art works. The intertextual links with both Marsden’s and Tan’s backlist of books, their international profile and the unique complexity of the storytelling here justify its inclusion in any database of narrative texts about Aboriginal Australians. Over 30 editions of this book, first published in 1998, signal the importance of this story.

The narrator of ‘The Rabbits’ is never named or identified - and that in itself is a metaphoric code for colonised Aboriginal Australian perspectives. The voice in the word text is childlike and bewildered. It tells an apparently simple story about the fascinating and dreamlike visitation of strangers, which rapidly turns into a nightmare invasion that threatens the existence of both the narrator’s people and their country. The imagery in the picture text is variously childlike and highly sophisticated, conferring on the story an engaging surrealism that invites individual interpretation by readers from primary school age to adult.

Readers familiar with John Marsden’s fiction will read the spare, almost taciturn nature of the word text as evidence of both trust and a watchfulness that comes from the experience of and the apprehension of hurt. The faux-naif font used to render the words is angular and backward leaning, as if fearing a physical blow. It appears to have been hastily scribed, or even gouged, into some unyielding surface such as wood or rock. This reaching for a language to describe the indescribable recalls the apocalyptic vision of such narratives as Russell Hoban’s ‘Riddley Walker’.

Readers of later texts such as ‘The Lost Thing’ and ‘The Arrival’ that made Shaun Tan the winner of many Australian and international awards for his storytelling will recognise the use of vast space and complex detail in the compositions, the ongoing conflict between the industrial and the elemental, and the highly referenced and at the same time startlingly new imagery - all of which make the narrative vibrate between dream and nightmare.

Young readers interested in visual literacy will find endless opportunities to explore detail in both imagery and design. The book begins and closes with lyrical, light endpapers, picturing the ‘great billabongs alive with long-legged birds’ lamented in the final pages of the word text. The palette becomes bleak as the invading rabbits drain vibrant colour from the land, and in one spread the sepia halftones and torn edges of the collage recall archival imagery, and imply that life has already gone, and that the land is beyond rescue. Still, the last page of Marsden’s word text challenges his readers with a question: ‘Who will save us from the rabbits?’ - thereby implying, perhaps optimistically, that the restoration of Country is possible.

The narrator’s community under attack are imagined as numbats: an Australian marsupial that was once distributed across the continent but was almost wiped out by introduced foxes. Characteristically, Tan’s choice is finely nuanced. Emblem of his home state of Western Australia, the numbat has a striped coat that immediately connects with one of its generic relations, the now extinct Thylacine (‘Tasmanian Tiger’). In one spread after another, the native inhabitants are tiny and crammed into a claustrophobic space on the margins of vast tracts of Country colonised by the rabbits. The stripes, though always visible, signal their vulnerability. Even the word ‘numb’, embedded in the species name, hints at their response to colonisation.

Equally iconic is Tan’s ever-present parody of the Union Jack, symbol of empire. Its familiar stripes morph into arrows hurtling out from the centre, directing acquisition at all points of the compass, looking one moment like a net, or spider’s web, another like octopus straps, jealously guarding material possessions from flying off in the wind. At the same time, like the invaders’ tracks, cruelly parodying songlines. There are mice in the harvest, steampunk combine-harvesters looking like Lost Things; there are dead numbats, already fossilised curled like nautilus shells deep in the scorched earth; discarded bottles that one moment seem to have contained the world’s most famous soft drink, the next alcohol or the apothecary’s endless remedies for the disease accompanying invasion.

As so often with the fable genre, the fewer the words in the text, the richer the potential layers of meaning, opening explorations of The Rabbits in the classroom far beyond the scope of these few annotations.

(Annotation first published in the Aboriginal and or Torres Strait Islander Resource)