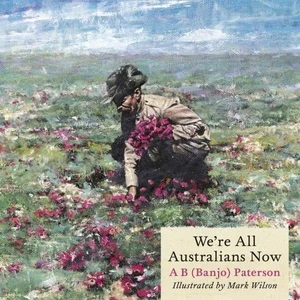

The cover shows an Anzac lighthorseman kneeling on an uneven plain that stretches to the horizon. He is intent on gathering poppies, of which he already has a huge bouquet. There’s a poignancy in the cover which should not be overlooked. The serviceman could be in a planned and manicured cemetery – but he is not. He is on a former blasted battlefield where the dead lie close to the surface.

Wilson is an artist who has specialised in memorialising Australian forces’ overseas campaigns. Many of his images are referenced by paintings and photographs with a full list of the originals included at the back of the book. His additional source material includes contemporary newspapers, sketches, maps and other visuals which he has rendered variously in pencil, acrylic paint on paper/canvas or pen and ink and sometimes a mixture of these. His process has democratised the differing media and furthers the central call of Paterson’s poem – that old colonial rivalries between separate states have been excoriated in the creation of the Australian Imperial Force.

The inspiration provided by this text ensures a traditional view of the courage and sacrifice of the armed forces. Clues in the poem are fleshed out by the artist, including personifying Australia as young and female. The female images are traditional – the young girl knitting the sock, the nurse, and Madonna and child beseeching either sacrifice or victory.

Paterson’s reputation as an important voice in Australian poetry ensured that there would be a wide audience for this poem. An important detail to note is that Paterson wrote this in 1915 – his hopes of being a war correspondent dashed, he had returned from driving ambulances in France to Australia. He returned to Europe and ended the war in charge of reallocating the surviving horses shipped from Australia.