Title

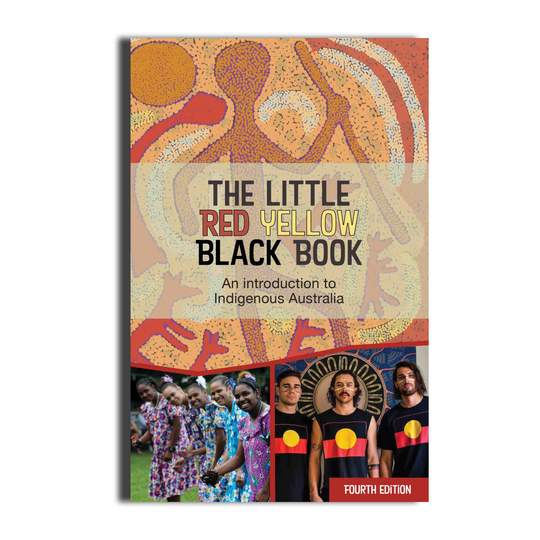

The Little Red Yellow Black Book : An Introduction to Indigenous Australia

Author

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Press

Secondary Authors

Bruce Pascoe

Illustrators

Amity Raymont, Design

Publisher, Date

AIATSIS Press, 2018 4th Edition (first pub 1994)

Audience

Secondary, Upper Primary

AC Links/EYLF

ACELA1500, ACELA1502, ACELT1608, ACELT1609, ACELT1610, ACHASSK107, ACHASSK108, ACHASSK109, ACHASSK110, ACHASSK112, ACHASSK113ACELA1500, ACELA1502, ACELT1608, ACELT1609, ACELT1610, ACHASSK107, ACHASSK108, ACHASSK109, ACHASSK110, ACHASSK112, ACHASSK113, ACSHE081, ACSSU083, ACAVAM114, ACAVAR117, ACADAM011, ACADAR012, ACAMUM089, ACAMUR091, ACPPS051, ACPPS053, ACPPS054, ACPPS055, ACPPS056, ACPPS057, ACPPS058, ACPPS059, ACPPS060, ACELA1515, ACELA1518, ACELT1613, ACELT1614, ACHASSK134, ACHASSK135, ACHASSK137, ACHASSK140, ACSSU094, ACSHE100, ACELA1528, ACELA1529, ACELT1619, ACELT1621, ACELT1622, ACELT1803, ACDSEH148, ACHGK041, ACHGK043, ACHGK046, ACSHE119, ACSHE223, ACSHE120, ACAVAM118, ACAVAR124, ACADAR019, ACAMUR098, ACPPS074, ACPPS075, ACPPS077, ACPPS078, ACPPS079, ACPMP085, ACELA1540, ACELA1541, ACELT1626, ACELT1627, ACELT1628, ACELT1807, ACHGK049, ACSHE226, ACSHE135, ACELA1550, ACELA1551, ACELT1663, ACELT1771, ACELT1634, ACELT1635, ACDSHE084, ACDSEH020, ACDSEH090, ACDSEH091, ACHGK065, ACHGK067, ACHGK069, ACSHE157, ACSHE160, ACAVAM125, ACAVAR131, ACADAR026, ACAMUM102, ACAMUR105, ACPPS089, ACPPS093, ACPPS098, ACPMP104, ACELA1563, ACELA1564, ACELA1565, ACELT1639, ACELT1640, ACELT1812, ACELT1642, ACELT1643, ACOKFH022, ACOKFH024, ACDSEH108, ACDSEH106, ACDSEH023, ACDSEH104, ACDSEH106, ACDSEH134, ACDSEH143, ACHGK071, ACHGK072, ACHGK076, ACHGK081, ACSHE191, ACSHE192, ACSHE194, ACSHE230

ISBN

9780855750527

Add to Favourites

-

Subjects

-

Annotation

-

Teaching Resources