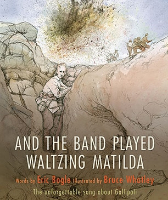

Published to commemorate the centenary of the 1915 Gallipoli campaign, ‘And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda’ pairs the lyrics of Eric Bogle's 1971 song of the same name with pen and watercolour illustrations by Bruce Whatley. The subtitle on the front cover tells us that this is not a song likely to be familiar to picture book readers now, although it is regarded as an Australian classic by their grandparents and parents: 'The unforgettable song about Gallipoli' it says. While the inclusion of that line suggests that, tragically, it might not be 'unforgettable' at all, it makes a significant point. Despite the loss of human life, and the destruction of the built and natural environments, humans still keep marching off to war. The quote on the back cover puts it succinctly: ‘We buried ours, and the Turks buried theirs; then we started all over again’.

Bogle says in an afterword that not long after emigrating to Australia from Scotland in 1969 while Australia was still at war in Vietnam, he attended his first Anzac Day march, and heard the song 'Waltzing Matilda'. The strange disconnect between the two inspired the song lyrics. This adds a further layer to the time scheme in the narrative: the romantic nationalist poet AB Paterson wrote 'Waltzing Matilda' in 1895. Its jaunty rhythm contrasts ironically with the subject matter of a swagman during the economic depression of the 1890s, tramping with his bedroll or swag in search of a home, a job and a meal. His swag is his dance partner, as he waltzes 'Matilda' across the grim landscape. It's a song that one generation of Australians wished had been made our national anthem: a strange choice perhaps, about a man who steals a sheep because he is hungry, then takes his own life rather than submit to police custody, and ends up as a ghostly presence forever.

Bogle's text takes us back to the 1890s, to one period of Australian mythmaking, to a second wave at Gallipoli, and connects both with a third wave in Vietnam, by which time any swagger associated with Australian masculinity, rebellion and patriotism has been thoroughly contested, if not discredited. The fact that Australia keeps going to war in locations that have more to do with politics than Australia's immediate security will not be lost on a generation of young people distressed by the war in Ukraine.

The ageing of the narrator in Bruce Whatley's illustrations tells the story of a young country that gets older but still doesn't learn, although individuals like him and his mates who are broken by the experience of war have learnt to ask what it was all for. In the second last illustration, Whatley zooms right in on the old soldier's face, with its lifeless eyes, its wrinkled skin and missing teeth and makes this confronting question inescapable.

Unlike other picture books on this subject, or the iconic Peter Weir film 'Gallipoli', Whatley never succumbs to the popular Anzac myth by portraying the young Australian soldier as a confident fresh-faced innocent. As the narrator looks at the reader from the front cover and in the first, ninth and twelfth spreads, he is young but troubled right from the start by the question that haunts him when he is old.

The softness of the wash illustrations and the muted sepia palette recalls archival illustrations and photographs and provides a nuanced contrast to the horror of the subject matter. The spattering on every spread of this now old and familiar story conveys exposure and the passage of time like the foxing of an old book, but it also suggests spots of blood everywhere, which has lost its bright redness - and some of the horror - with the years. Again ironically, there is almost no blood-red tint in the visual narrative: the most we get to see is around the file of maimed troops returning home, and on the medals and commemorative poppy at the final march. Whatley's restraint makes the story more thoughtful and probing than sensational. Among the memorable images are the leggings in the second spread that predict the bandages we see when the narrator loses his legs, and the way the men's bodies morph into the hospital blankets, the open trenches and into the vastness of the earth. Unforgettable.