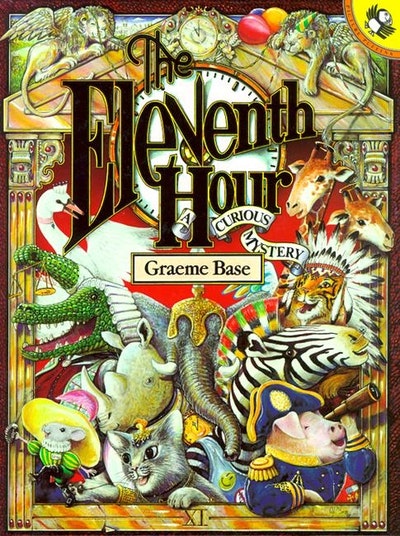

In ‘The Art of Graeme Base’ (2008) Julie Watts, one of his publishers, says that the author had the idea for ‘The Eleventh Hour’ while travelling in Africa and Europe and reading Agatha Christie. He did not want to repeat what he had recently done in ‘Animalia’ (1986), but a murder mystery was not going to be acceptable in a children's picture book. The crime of stealing the food for a birthday party, however, would appeal to young readers, so the story is about Horace the elephant, who is turning 11 and invites 11 guests to his party. He is a champion baker, prepares an amazing feast and the party will take the whole morning, because there are 11 games to play first. Then, at 11 o'clock, finally they will get to eat. But when they race up the 11 steps to the banquet hall, they discover to their horror that the feast has been eaten and the place is in chaos.

Who is the thief? While each guest denies being responsible, Horace whips up a pile of sandwiches, and brings out the birthday cake - which the thief has missed because it was hidden - and they have a wonderful day after all. But they never do find out who stole all the food. The narrator tells readers that the clues are there in the visual narrative if they just look carefully. So the book itself and solving the mystery is in fact a 12th game.

Although originally separate, for the Puffin paperback full notes on how to solve the mystery and read all the clues in the illustrations were bound in after the final coded 'Notes for Detectives', which tell us that the culprit is Kilroy the mouse, one of the guests, helped by 111 of his friends.

‘The Eleventh Hour’ amply confirmed the international success of Animalia as a virtuoso example of Graeme Base's art, but the most interesting question is why this book? Why now? The year of publication 1988 positions ‘The Eleventh Hour’ just after Martin Handford's ‘Where's Wally?’ (1987). A work of this complexity could not possibly be influenced by a book that also was to become a commercial phenomenon - what would later be termed a 'franchise'. So we have two examples of the late 1980s zeitgeist - both responding to the new emphasis on literacy and visual literacy - demanding that we read in detail, and keep turning the pages.

But visual literacy was just part of a general concern with literacy - particularly among adults caring for boys. Paul Jennings' first book ‘Unreal!’ (1985) used short stories, comedy, and surreal plot twists to engage readers who lacked confidence - earlier stereotyped as 'reluctant readers'. ‘Putrid Poems’ (1985) by Jane Covernton and Craig Smith followed June Factor and Peter Viska's series of playground rhyme collections with scatological humour that challenged the impression that children's literature was too well-behaved. And in 1986 the plot of Gillian Rubinstein's ‘Space Demons’ seemed to warn about the dangers of children getting lost in the new digital space.

In that context and although not overtly political like some of Graeme Base's later picture books, ‘The Eleventh Hour’ seems to remind us that reading can be a page-turning compulsion, it can be funny, cheeky, colourful, mysterious, it can test our powers of observation and thinking, and it reminds us that the whole process can be energetic and interactive. A far cry from the image of reading as a passive school-driven obligation, no longer likely to appeal to today's active children. (Neil Postman's 1985 title ‘Amusing Ourselves to Death’ responded to the adult preoccupation with entertainment.) In some ways, then, this is a very modern book - maybe even postmodern - but the visual style and the games almost seem like a rearguard action to reclaim a past tradition at the 'eleventh hour' - the last minute - just before the digital revolution really hits and consumes everything.

All that said, ‘The Eleventh Hour’ is still an exuberant and unmatched example of the picture book as parlour game!